From the wading pool to the diving pit: Deep Ecology

Nausicaa's secret garden. In the film, Nausicaa understands that her people can only survive by living in harmony with nature.

Photoggram from “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind”, Ghibli Studios, 1984

For thousands of years, humans have questioned our relationship with the environment around us. The Western view is that humans are the pinnacle of evolution, and therefore nature is at our service to be exploited. Needless to say, this has led us to the planetary crisis we are currently experiencing.

Industrialism is based on a vision of nature at our service.

“Man as controller of the universe”, Diego Rivera, 1934.

On the other hand, there are nuances in the ways we can care for or identify with other forms of life on our planet. For many, humanity has incurred a debt by ruthlessly extracting resources, and it is therefore time for humans to transition from being exploiters to caretakers of nature. In the 19th century, thinkers such as John Muir laid the foundations for environmentalism and National Parks. Almost a century and a half later, the UN has recognized that the entirety of humanity’s wellbeing depends on the benefits we obtain from nature, which we call ecosystem services. In this worldview, we recognize that if we want to be prosperous, it is essential to care for nature.

However, there is a growing group of people who recognize that this ecological vision is paternalistic and insufficient, and that we can go much further. The forests and mountains that John Muir wanted to protect were not empty, as he believed, but were territories cohabited by indigenous communities. For example, in Mexico, we no longer create National Parks as cabinets of curiosities, but rather Biosphere Reserves to manage both the biological and cultural heritage. George Caitlin, a contemporary of Muir, recognized this, as he wanted to create a “park containing man and beast in all their wild and freshness of their nature’s beauty.” Caitlin, although deeply rooted in colonialism, understood that the boundary between the natural and the human is much more blurred than we might believe at first glance.

John Muir was instrumental in protecting Yosemite National Park in California.

“Winter Storm Clearing,” photograph by Ansel Adams, 1937

Until now, we have been treading in the shallow waters of environmentalism, and this question brings us to the edge of the precipice. To leap into the deep waters, we only need to consider what are the consequences of there not being a real boundary between the natural and the human. Seen under this light, humans are just another living being, no more valuable than a cow, a tree, or even a bacterium. We all belong to life on Earth and have a fraternal relationship with every other being that shares this home with us. Thus, we should not care for forests because they are beautiful or because they give us drinking water, but because each tree is unique and irreplaceable, and because the forest provides water to all the species that inhabit it. Every being and its life are valuable simply because they exist, without that value depending on their relationship with us. Furthermore, life on Earth as a whole is valuable, as is how we all contribute to and form part of it. Lynn Margulis and James Lovelock extensively studied this collective behavior of terrestrial life for the preservation of vital wealth and named it the Gaia hypothesis.

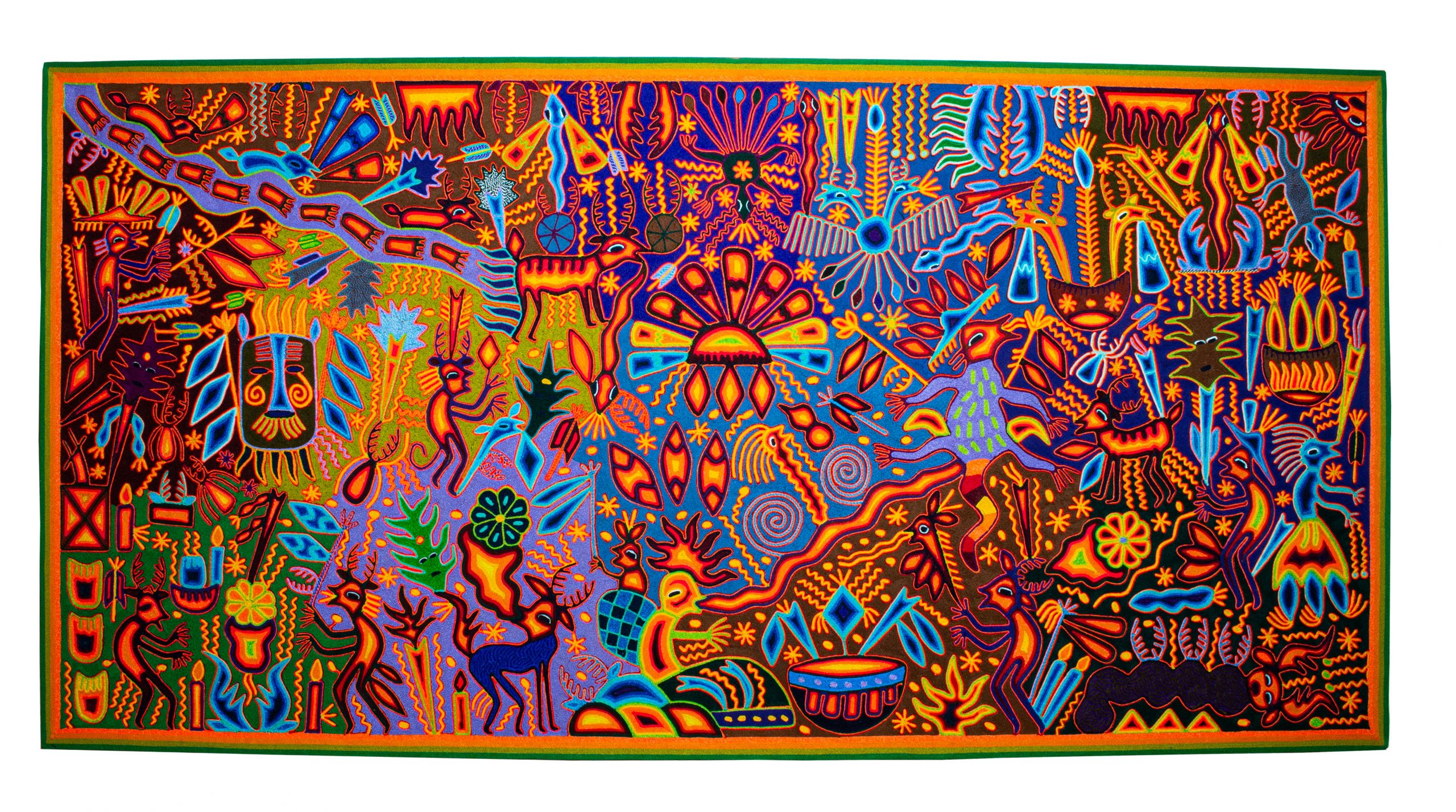

Indigenous communities have always understood that we are part of the land.

“The Wixarika Cycla”, Nierika Board by Lourdes Benitez, Mesa del Nayar community, Nayarit, Mexico

Arne Naess proposes that, like any other living being, humans have no right to reduce this wealth except to satisfy our basic needs, and that our current interference in Gaia’s cycles is excessive. At this point, we recognize our capacity as destroyers of the environment, but not our paternalistic responsibility to protect it. On the contrary, our responsibility is to radically transform our livelihoods in order to coexist as just another link in the deep web of life on Earth.

Article translated from Spanish with DeepL, proofread by a human

Article published originally in Spanish in the Izcalli Times